It has been well established that women experience increased vulnerability to mental ill health during pregnancy and the postpartum period (Megnin-Viggars et al, 2015). The further vulnerability of marginalised groups in the perinatal population, such as women from migrant or minority ethnic backgrounds, is also known (Falah-Hassani et al, 2015; Moore et al, 2019). The COVID-19 pandemic led to a significant mental health burden, with depression and anxiety being higher in perinatal women during the pandemic compared to prior to the pandemic (Hessami et al, 2020). This has been felt more acutely by populations who were already more vulnerable to mental ill health (Das, 2021).

Perinatal mental ill health impacts both maternal and infant health outcomes. In the UK, suicide as a result of maternal mental ill health has been a leading cause of maternal death in recent years (Knight et al, 2021). Furthermore, negative associations have been found between prenatal anxiety and breastfeeding initiation, and between postpartum anxiety and the duration and exclusivity of breastfeeding (Hoff et al, 2019). Women with postpartum depression are also less likely to breastfeed at all or exclusively (Wouk et al, 2017), with one study reporting that postnatal depression pre-dated discontinuation of breastfeeding, but not vice versa (Dennis and McQueen, 2007). A meta-analysis found that maternal perinatal depression or anxiety increased the risk of poorer infant socio-emotional development, including internalising, externalising and negative emotionality (Rogers et al, 2020). Perinatal mental ill health was also associated with poorer infant language, motor skills and cognitive development, with these deficiencies not only noted in infancy but into childhood and adolescence (Rogers et al, 2020). These long-term impacts for both mother and infant mean that effective management of perinatal mental ill health is essential.

Peer support is frequently used to describe the support provided by someone who has faced common experiences (Jacobson et al, 2012). It has been used in many aspects of maternity, including one-to-one support in labour, breastfeeding and perinatal mental ill health (Jones et al, 2014). A meta-ethnography of five qualitative studies found women described peer supporters for perinatal mental ill health as beneficial (Jones et al, 2014). Peer supporters were valuable to help women towards recovery, as the supporters helped them to overcome their sense of isolation, validated the feelings they were experiencing and were someone with whom the woman did not feel they had to pretend that everything was alright (Jones et al, 2014). Peer support interventions for new mothers with postpartum depression have found mixed results, with some interventions reducing depressive symptomatology and others not finding any impact (Leger and Letourneau, 2015). However, the need for peer support interventions to take into account a mother's culture as well as linguistic differences, has been highlighted (Leger and Letourneau, 2015).

A paucity of volunteers from ethnic minorities has been noted in the local area of this study. The project presented in this article brought together Light Pre and Postnatal Support (2022) and Sheffield Hallam University. The charity organisation, Light Pre and Postnatal Support, run a successful and established peer support model to support women with perinatal mental ill health and their families. Sheffield Hallam University has an academic team with expertise in interventions to support migrant and ethnic minority women in the perinatal period. This expertise was developed through a previous project, the operational refugee and migrant mothers approach (ORAMMA), which was designed to develop and test implementation of an integrated maternity care model involving maternity peer supporters to enhance the care of migrant mothers and babies who had recently arrived in European countries (Fair et al, 2020; 2021; Soltani et al, 2020).

The project produced an ongoing legacy in Sheffield, in the form of the self-organisation of maternity peer supporters to liaise with other third sector organisations and charities to continue to provide support to members of their community. They were known as ORAMMA maternity peer supporters or ‘friendly mothers’. The expertise of both Light and the friendly mothers was combined to develop a training package to help peer supporters support women from ethnic minorities with mental ill health. This article evaluates the training package developed from the perspective of peer supporters.

Methods

Training

The project was based on the amalgamation of existing training packages offered to women who wished to volunteer as a peer supporter with Light or as an ORAMMA maternity peer supporter. The Light training focused on perinatal mental health and ORAMMA training focused on the needs of migrant women in the perinatal period. Adaptation of the training packages was carried out through multiple consultations between Sheffield Hallam University, the friendly mothers and Light partners, to improve cultural sensitivity and highlight issues that may be especially pertinent to women from migrant and ethnic minority backgrounds.

The training package included lectures, scenario-based learning, group discussions and mini lectures. The topics covered in each session are shown in Table 1. Training was co-facilitated by experts in each of the topic areas, who were able to share their own personal and professional experiences to contextualise theoretical learning. Additional information was given to the trainees to enable them to further explore the issues raised at home.

Table 1. Session content

| Time | Content | Format |

|---|---|---|

| Day 1 |

|

|

| Day 2 |

|

|

| Day 3 |

|

|

| Homework |

|

|

Training was delivered across three sessions, each lasting 2.5 hours. It took place in England during March 2021, when the country was just emerging from full lockdown restrictions from the COVID-19 pandemic and coinciding with the 1-year anniversary of the first UK lockdown. This meant that participants were currently affected by restrictions and could also reflect on the impact of the pandemic over the preceding year. As a result of the restrictions in place, in-person training was not possible, and training was delivered digitally using Microsoft Teams. Training was facilitated by staff from Light and the friendly mothers, with a member of staff from Sheffield Hallam University attending sessions to make observations and provide support if required.

Participants

As the nature of this project was to pilot and evaluate combining the existing training programmes, participants were recruited from current volunteers, five of whom were Light peer supporters and five of whom were former ORAMMA maternity peer supporters.

Data collection

Evaluation was undertaken in two phases. The first phase involved asking participants to complete a brief evaluation questionnaire immediately after the training course had been delivered. This asked a combination of multiple choice and free-text response questions.

The second phase collected additional feedback via a focus group discussion 3 months after the end of the training course. This focus group was attended by two training participants and two training facilitators. A further training participant requested an individual interview (because of other commitments), which was undertaken on the same day. This further feedback followed a period of reflection and therefore allowed for additional insights on whether the training had influenced the participants personally or in their practice. The focus group and interview were audio recorded.

Analysis

Quantitative data collected from the evaluation forms were evaluated using descriptive statistics. Qualitative data from the open-ended survey responses were combined with data from the focus group and interview. Three authors (GO, FF, HS) familiarised themselves with the data and then identified themes within the responses using thematic analysis. This process was initially undertaken independently, with the three authors then coming together to agree on the final themes.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was obtained for this service evaluation prior to commencing the project (ER31498925). Participants were sent a participant information sheet and consent form prior to the focus group/interview. Given the electronic method of data collection, verbal consent was then taken from participants at the beginning of the focus group/interview. Participant numbers only have been provided alongside quotations to protect confidentiality.

Results

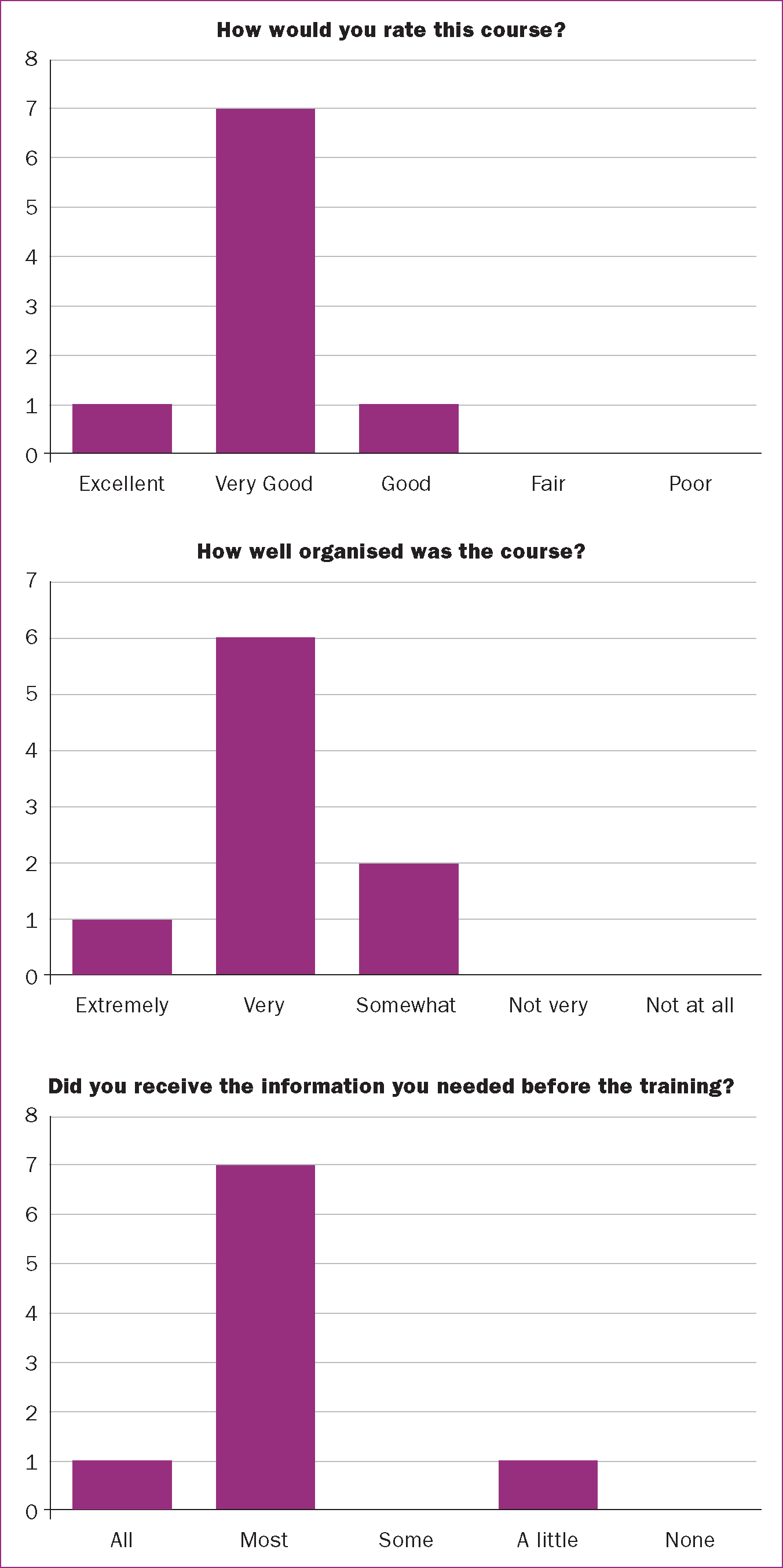

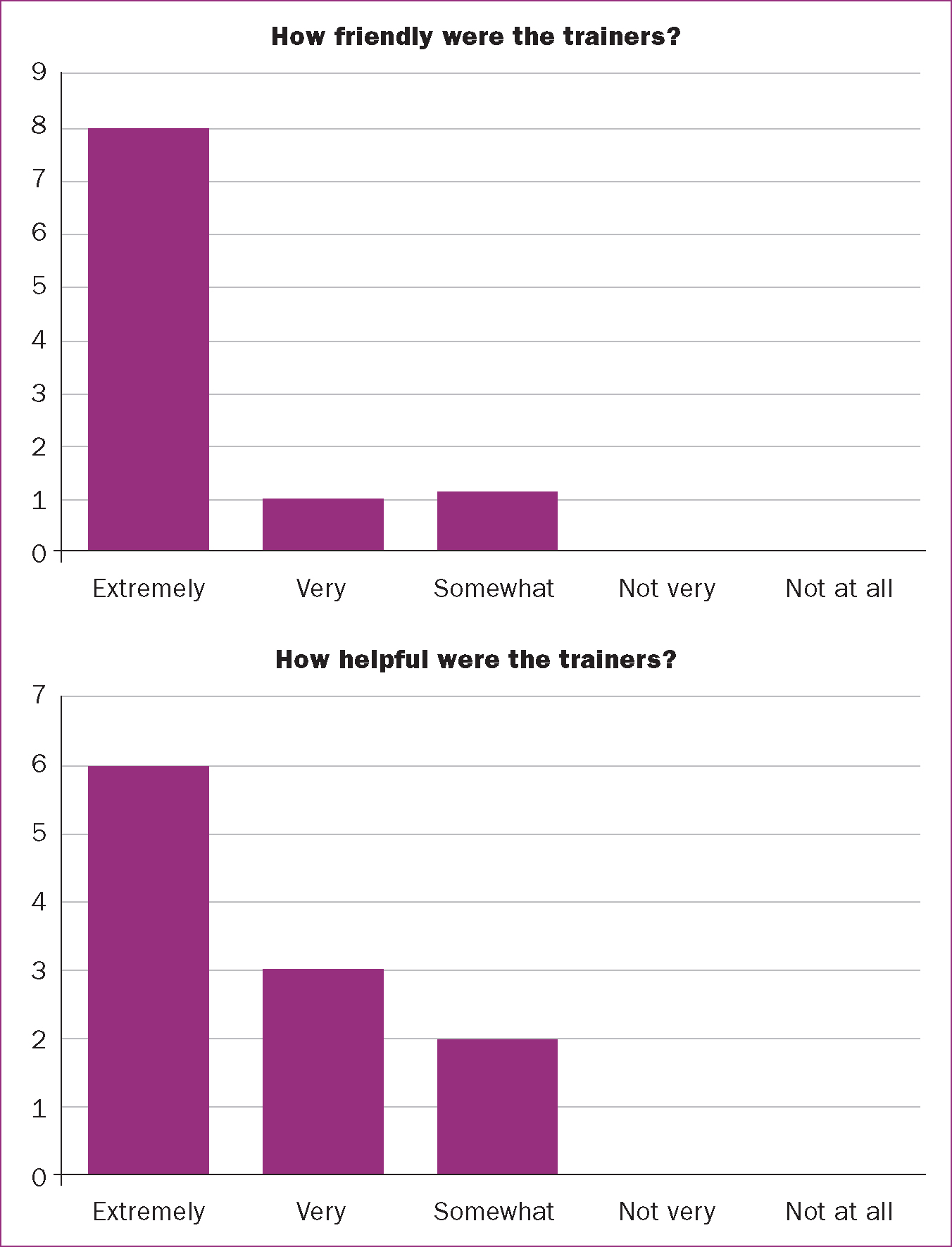

A total of 10 peer supporters were trained, with nine women completing the evaluation form. This immediate feedback showed that the training was generally well received. The majority of participants rated the course as ‘very good’ and none considered it to be ‘fair’ or ‘poor’ (Figure 1). Participants reported that the trainers were friendly and helpful (Figure 2). When asked about the organisation of the course, two participants felt the course was only somewhat organised, with the remainder feeling it was well or extremely well organised. While most participants felt they had been provided with all or most of the information required prior to the training session, one woman felt they only received a little of the information required.

Within the qualitative data, three overarching themes were identified: ‘training positively received’, ‘training challenges’ and ‘learning and development’.

Training positively received

Enjoyment of learning

Participants reported the training to be interesting and clearly presented, and they appreciated being able to learn new things. The trainees also liked being able to participate in an activity that took their focus off the national COVID-19 restrictions at the time.

‘It was very interesting and I did enjoy it a lot personally.’ I3

‘Lovely trainers and a well-presented presentation.’ S6

‘I also really enjoyed it, because I personally learned lots of new things through it as well, so it was really good training for me.’ I1

‘It was, I think particularly the time that we did it, it was very nice to be doing something that took you away from immediately what was going on [COVID-19 lockdown and restrictions].’ I3

Group discussions

Participants found the use of training scenarios particularly helpful in developing their understanding of the issues and how peer support works in practice. In particular, the group discussions between participants around these scenarios were viewed positively. The friendly nature of the training environment and the female-only dynamic of attendees was appreciated, as trainees felt it helped them to be more open during the discussions.

‘I found the scenarios really helpful in making me think how I would act in the role and the task around report writing very useful in a practical sense.’ S4

‘We have built a good friendship and the information was beneficial to all of us.’ S5

‘That's the best thing of it, we're all ladies there, so even if we suddenly get our scarf off or something, its OK, so we feel free, we talk more openly, you don't hesitate…when you're with women, you are more open about your feelings about what you think.’ I5

Training challenges

The training was not without its challenges, including technical issues, lack of scenario complexity, course length and home learning activities or other commitments.

Technical issues

The main challenges encountered were the result of technological issues. This was a particular problem during the first session, making session delivery disjointed and meaning some participants had to re-join the meeting several times. These were addressed as far as possible between sessions, meaning the second and subsequent meetings ran more smoothly. Trainees were concerned that these technical issues might have led to them missing out on parts of the training. Remote delivery of the training course was also not the preferred mode for any future training, as trainees felt it limited discussions between them, which could enhance their learning.

‘I struggled with the course being over Zoom but this is only due to the pandemic.’ S1

‘I found the breakout rooms stressful because of technology, as you were not sure whether you would reach them.’ S3

‘That [struggling with breakout rooms] made you feel that you were kind of isolated but also that you'd missed something and you were worried about how important this was. You felt perhaps you weren't as well trained because you missed bits.’ I3

‘I think we might have missed some of those really rich conversations, which flow quite easily if we'd have been face-to-face.’ I2

‘I really like training when everyone is gathered together and shares ideas and be involved in everything. The computer doesn't really do much, but in the end it wasn't bad, I'm pleased we did something.’ I4

‘Doing it on the computer, I would say, for me, I would have so much preferred to do it face-to-face.’ I3

Lack of scenario complexity

There was a call for more complex scenarios during training that more closely reflected what participants saw in reality, including women having multiple challenges and difficulties that could be further impacted by their culture and religion. Trainees also reported wanting more time to gain a better understanding of the scenarios presented, ideally with practical examples of organisations that the peer supporter could refer women to in different situations.

‘I know there was limited time that we had, but specifically for the mental issues that we had, if there were more practical examples…to understand them more deeply, because afterwards you are supposed to be a trained person that you will go and face these mental issues, so if you had examples at the back of your mind it would be much better.’ I1

‘I would have liked a bit more time to reflect on the scenarios with a list of possible contact organisations we can use and when that may be necessary… a bit more discussion perhaps.’ S3

‘There weren't scenarios that was like very real situations. After we finished the training, I had a lady who contacted me, she couldn't get anywhere, she was really in tears.And she was talking to me and she said “I can't get hold of advice bureaus, I can't get hold of GP. I'm pregnant, and I'm having problems with my partner, my partner wants to send me back home"…all these things. And it reminds me of some of the scenarios that we practised on the training, but they didn't really involve the culture or the community background. We haven't gone into depth about culture, religious things, things that are beyond your control.’ I5

Course structure

One participant who had previously attended whole day training sessions, felt that the shorter sessions given during training enabled better retention. However, others still found the considerable amount of information provided each week to be a challenge and would have preferred the course to have run over more time to allow for more discussion around each topic.

‘With this training, I felt I was able to concentrate and retain more information because of the format of delivery -shorter sessions over a number of days, rather than one long day.’ S4

‘There was a lot to take in each week and lots of stuff that I didn't know about at all…I would have liked it to be longer, but I think this is to do with being online. There was an awful lot in each session and perhaps if we were face to face there would have been more discussion.’ I3

While some liked the home learning provided, as it gave them an opportunity to consolidate their learning, others found it difficult to motivate themselves to do it and would have preferred to cover it in additional face-to-face sessions.

‘I enjoyed the home learning as it helped keep me involved in what we were learning between sessions.’ S4

‘I didn't like the homework thing, and that's obvious because I haven't done all of it yet. I would have liked that to be more incorporated into the training.’ I3

‘The training that I like to participate in is having stuff to do in the groups during the training time. I enjoy it more than just doing some stuff by myself in my own time as a homework thing.’ I1

As noted in the quantitative evaluation, while some participants felt that they had received enough information prior to each session, others would have liked more information, for example, lesson plans.

‘Not having enough notes before about scenarios…[it would be] useful to have a plan of the session beforehand.’ S9

Other commitments

Women reported multitasking because of other family commitments, especially during the COVID-19 lockdown. This meant that some women found they were interrupted during the online course by circumstances around them at home. Furthermore, one woman felt that training reminders would be beneficial in the future, as the training could be forgotten in among the business of life.

‘Because we are doing so many things, we forget there is training. If we get a text message to say “log in now” that would be great.it would have been good if we had a hint maybe the day before, or maybe the same day, just a reminder.’ I5

‘I used to listen to everything, but I'd mute myself and follow…so you're multitasking... and then you've got one ear listening to other people and one ear is on the speakers.’ I5

Learning and development

Participants’ learning and development was a significant overarching theme, with feedback predominantly gathered under two sub-themes: ‘increased awareness’ and ‘personal and professional development’.

Increased awareness

Given that this pilot project integrated two existing training packages, with participants drawn from both specialities, it was not surprising that participants reported their learning to mainly align with the topic in which they had not previously been trained. Learning was focused on the range of mental health issues that may affect women perinatally and on the impact of migration on women's experiences.

‘I really, really did learn a lot about different cultural values and I found the parts of the ORAMMA training which were incorporated about migrant women and the reasons for migration…really interesting and think that would be something I can definitely take forward in offering support women.’ I2

‘I learnt a lot about how to support migrant mothers, what barriers they may face and how I may have to tailor my support of them to be of help. This is an area I had no prior knowledge of thank you.’ S4

Several participants reflected on the overall vulnerability of women at this stage of their life and how the experience of pregnancy and new motherhood could contribute to perinatal mental health difficulties.

‘For me personally I only knew about post-birth that you get depression, but I really didn't know there are so many mental illnesses that a mother can face after giving birth.’ I1

‘How much mental health issues are important, especially for a pregnant women or mothers, and how much we can help with it.’ S8

‘[I learned] all about the higher suicide rates, you know the maternal deaths. That was all quite shocking and quite hidden in a way.’ I3

‘I think it's just given you an awareness of women and what women who have children, ordinary women, what they go through…And the vulnerability of women when they are having children and how women, mothers particularly, don't get enough attention.’ I3

‘For 9 months you are precious, then you're thrown beyond the backburner.’ I2

Participants reported that the ability to learn from each other and consider alternative perspectives was very valuable.

‘I am finding it very helpful, bringing organisations together brings additional understanding and knowledge to integrate services and bring about awareness of wider issues.’ S7

Personal and professional development

The training provided participants with an opportunity to meet with and learn from a group of diverse women with a common goal of supporting other women. This led to a better understanding of their role as a peer supporter. In particular, trainees felt they gained skills around how to support women effectively in a non-judgemental and sensitive way, to be empathetic and to be a good listener.

‘It was very strong on getting us trainees to appreciate the sensitivity of our work and to be cautious about our sharing and approach.’ S3

‘During the training, you learn you shouldn't be judgemental when you come up to a mother that is suffering from some mental ill health issues. So not being judgemental, trying to be a good listener. You always have these things at the back of your mind, but having it repeated to you to remind you every time.’ I1

‘It definitely gets you to think about women and their position, women that you know that have been depressed … it gives you more empathy.’ I3

‘You shouldn't be judgemental, just a good listener, especially with the migrant parents, she just needs someone to listen to her story and support her. It's very important as a peer supporter.’ I4

They also learned the importance of addressing both a woman's mental health issues and any issues she may be facing because of migration.

‘It made me bit reflective about a lady that came along.she was from Syria and had come to the country as a refugee. It led me to reflect, if I had done the training and had a better knowledge of migrant women, could I have better supported her with her mental health?’ I2

The focus on self care was also felt to be beneficial, to ensure they could be fully effective as a peer supporter.

‘I thought highlighting self care was really important to helpers.’ S4

‘Looking after yourself, I know we are committed with homes and kids, schools, pandemic, testing, tracing.but you need to feel good about yourself, that's a really important thing…it makes you feel you are valued.’ I5

Discussion

While previous research has explored the effectiveness of peer support programmes for women with or at risk of perinatal mental ill health (Jones et al, 2014; Leger and Letourneau, 2015; Shorey et al, 2019), there is limited literature evaluating training programmes provided to peer supporters. Where this has occurred, training has been rated positively by peer supporters, including among peers supporting women at risk of postnatal depression (Dennis, 2013) and those supporting people experiencing infertility issues (Grunberg et al, 2020). Similarly, the present study's evaluation of a training package provided to maternity peer supporters showed that the training was largely positively evaluated.

Trainees reported learning a lot during the course, which they could recall when interviewed 3 months later. However, most would have preferred face-to-face training. They especially felt that discussions were reduced by using an online format. However, the importance of interaction even within these online sessions cannot be underestimated. Previous peer supporters trained exclusively via self-learning materials and a pre-recorded webinar, while appreciating the flexibility, felt that the training could have been enhanced with a video conference of some sort (Grunberg et al, 2020). A meta-analysis found satisfaction to be lower when sessions were delivered via video-conferencing technology compared to face-to-face training (Ebner and Gegenfurtner, 2019). However, the effect on participants’ learning, assessed through post-training knowledge scores, was minimal. Therefore, while a face-to-face format in the future could enhance participant satisfaction, providing interaction through video-conferencing technology can be considered an acceptable alternative for effective learning.

Wide variation in the length of peer supporter training has been noted across perinatal peer support projects, with uncertainty as to what is deemed necessary to be a ‘professional friend’ (McLeish and Redshaw, 2015). Peer supporters trained to support people struggling with infertility have reported that they wanted shorter training, despite the training being 4 hours long (Grunberg et al, 2020). In contrast, in a study of peer supporters helping women at risk of perinatal depression, a quarter wanted training to be longer than the 4 hours they received (Dennis, 2013). They wanted to cover some aspects in greater detail and to include more role-playing or scenarios (Dennis, 2013). Similarly, peer supporters within the present evaluation desired longer training, despite it already being longer than the training provided in the study by Dennis (2013).

Peer supporters appreciated the opportunity to learn more about the impact of migration and culture on women. Migrant women are a heterogenous group with individuals varying in length of stay in a country, residency status and reasons for migration (De Grande et al, 2014; World Health Organization, 2018). As a result, health needs and outcomes for this group are complex, being determined by access to determinants of health in the country of origin, during transit and in the destination country (World Health Organization, 2018). Women from migrant backgrounds, in particular those with refugee or asylum seeker status, may have experienced traumatic life events (Fair et al, 2020). They are also more likely to experience a sense of isolation, be of poor social economic status, live in poor housing conditions and experience stress from the insecurities of their migrant status in the host country (Fair et al, 2020). All of these factors have been linked with increased mental ill health (Anderson et al, 2017).

Migrant women have described having different expectations of care influenced by both their experiences of care in the country of origin, as well as their cultural preferences (Fair et al, 2020). Interactions with culturally incompetent care providers has previously been noted to impact women from ethnic minorities in terms of their ability to access adequate support for their perinatal mental health (Watson et al, 2019;Watson and Soltani, 2019). Being aware of the additional challenges faced by many of these women can help to provide effective support. Trainees in the present training project appreciated learning about different cultural values and clearly stated that they had not thought about the impact of the migration journey previously. They could see how it would directly impact on the support they could provide to migrant women.

Strengths and limitations

A small number of peer supporters participated in this initial training course and only half completed the evaluation after 3 months. Furthermore, all had previously had some experience of providing peer support to women in the perinatal period. Staff turnover and sickness in the organisations also made communication in this project more difficult.

However, despite its small size, this evaluation showed that combined training on mental health and migrant women's experiences was possible. It was rated highly by participants, as they realised knowledge on these aspects would assist them to provide better peer support for women. The training provided significant insights into the preferred format and content of such training, with participants wanting face-to-face training with more scenario-based materials and additional time for reflection. In the future, further evaluation will be needed, including among participants that are new to peer supporting.

Conclusions

Partnering a research project with a charity organisation provided an exciting opportunity to improve support services particularly for perinatal mental healthcare. The combined training approach was reported to have multiple advantages, not least of which being the opportunity for participants from different personal and professional backgrounds to learn from each other. The development of integrated care services is of paramount importance in ensuring that relevant services are made available to the most vulnerable populations.

Key points

- Perinatal mental health peer support training was adapted to meet the needs of women from migrant or minority ethnic backgrounds.

- A total of 10 peer supporters undertook training and evaluated it through a survey and interviews.

- The training was largely positively reviewed, with peer supporters reporting enhanced understanding of perinatal mental health needs and the needs of migrant or ethnic minority women.

- The opportunity for participants from different personal and professional backgrounds to learn from each other was seen as an advantage.

- Further development of integrated care and voluntary services is of paramount importance to ensure that services are available and acceptable to the most vulnerable populations.

CPD reflective questions

- What factors may impact access to perinatal mental health services for women from ethnic minority backgrounds?

- What additional needs might migrant women or women from a minority ethnic background have when seeking or receiving care for perinatal mental health needs?

- Think back to a time that you cared for a migrant woman or woman from a minority ethnic background with perinatal mental health needs. How did it go?

- What further steps might you take to support migrant women or women from a minority ethnic background with their perinatal mental health?

- Are peer supporters used in your work setting and if they are, have they received training to provide culturally sensitive perinatal mental health support to migrant women or women from a minority ethnic background?